In an address to the United Nations General Assembly in 2012, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, Olivier De Schutter, spoke about the major threat “Ocean Grabbing” poses to small-scale fishers. For the first time, the UN used a term which progressive movements had used for years. But little has been done to unpack its meaning, understand its scope and assess its impact. In this story, we explain what Ocean Grabbing is.

Ocean Grabbing is not confined to the oceans – as the term may suggest. It is essentially about the grabbing of marine and land natural resources that small-scale fishers depend on for their livelihoods and food sovereignty. Food sovereignty means peoples’ democratic control over the production, processing, marketing and consuming of food. In the case of fisheries, it relates to all types of food that is harvested, caught or produced by people from the fishing communities. The grabbed resources include fish, shellfish, seaweed and other plants and animals harvested or caught from oceans, rivers and lakes. Ocean Grabbing affects both inland and coastal communities.

Before the ‘grabbing’ takes place, the small-scale fishing communities have reasonable access to and control over natural resources. This often includes traditional forms of ownership and long established rules for controlling and managing these resources. Rich and politically powerful companies and people use their connections, their enormous financial capital and even violence to ‘grab’ the natural resources. In this process, all democratic practices are abandoned and fishing communities become oppressed by political and economic elites. Traditional fishers are displaced and denied access to sea and land. Cultures, traditions and lives are lost.

In Ecuador, 70 percent of the country’s original 360 000 hectares of mangroves have been grabbed by the corporate shrimp farmers, the tourism industry and other actors, resulting in the displacement of tens of thousands of fishers. Mr Lider Gongora from C-CONDEM, the Ecuadorian member of the WFFP explains that “the estuary has become a war zone, and shrimp farmers even use packs of dogs and armed militias to protect their farms”.

Typically, the ‘grabbers’ are national and transnational companies, rich individuals or nation states seeking to exploit natural resources for their own profit. There is usually little respect for people or nature. Actions include the grabbing of fish stocks, coastal land for tourism projects and large-scale industrial agriculture and coastal zones for sea bed mining, oil drilling and other extractive industries. There has also been the destruction of mangrove forests for industrial shrimp farming, the appropriation of land areas for coal or nuclear power-plants as well as river areas for the construction of large-scale hydro-power dams.

In Bangladesh, there is an increasing demand for electricity. In response, the government has developed a coal-power plant just north of the world’s largest mangrove forest, the Sunderbans. The project is run by state-owned energy companies from India and Bangladesh, and there has been no real consultation with people who will suffer from pollution. Mr Mujibul Haque Munir, co-ordinator of the Bangladesh Fish Workers Alliance and member of the WFFP warns that “flooding will be more frequent and make more coastal land unsuitable for farming. Also, salt-water intrusion in freshwater supplies will lead to shortages of drinking water”. All of this will negatively affect the five million people living in the Sunderbans area.

The grabbing of the natural resources is made possible by the neo-liberal policies pursued and agreed to by nation-states around the world. Some of these policies take the form of trade and investment agreements between two or more states. It is through these kinds of agreements that foreign companies, states or individuals manage to grab resources around the world. In today’s entrenched global neo-liberal system, it is clear that decision-makers in the Global South and North increasingly align themselves with the interests of national and transnational corporations. Together this alliance dictates national and international policies and agreements behind closed doors, without meaningful participation of social movements.

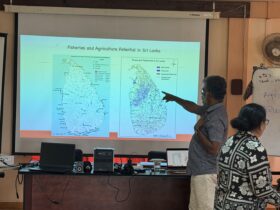

In the Kalpitya peninsula of Sri Lanka, 2 500 families have been evicted from their land to make way possible holiday resorts and five star hotels. The convener of the National Fisheries Solidarity Movement, Herman Kumara, observes that “the political consciousness of fisher people is on the rise and this of greatest importance in the struggle against the grabbing of the land and the sea.”

Yet, it is important to underline, that national governments – or sovereign states – have the right to reject policies and agreements leading to Ocean Grabbing and instead pursue people-centred policies that build on the principle of social, economic and environmental justice.

To counter Ocean Grabbing – and enforce democratic control and food sovereignty – we need to hold our own decision-makers accountable and enforce a radical shift in policy orientation. Our own governments – from local to national level – can make this possible, but only if we mobilise and fight back against this full frontal attack on our communities and way of life.

[button link=’https://wffp-web.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/The_Global_Ocean_Grab-EN.pdf’ size=’large’ color=’blue’ target=’blank’]Read the Ocean Grabbing Report[/button]

1 Comment