From farms and forests to seas and waterways, natural resources are under attack. Ocean grabbing, the overall process of enclosure of marine, coastal, and inland fisheries is an increasing threat to fishers around the world.

Today, delegates from some 42 member countries of the World Forum of Fisher Peoples (WFFP) are gathered in Delhi for the seventh general assembly of their collective movement. Leaders from the fishing community in India are also present, representing nine Indian coastal states and WFFP’s host and member organization, the National Fishworkers Forum (NFF). Resistance to ocean grabbing is a key working area and priority for WFFP.

“Ocean grabbing takes away people’s customary rights and traditional way of living,” stressed Herman Kumara, Special Convener of the Sri Lankan National Fisheries Solidarity Movement (NAFSO) and a leader within WFFP. He specified that ocean grabbing takes place through militarization, financialization, or conservation processes, evicting people from their territories.

Delegates to the assembly shared the different forms that ocean grabbing takes in their countries. “In my country, grabbing takes place through policymaking and is deeply institutionalized,” said Christiana Louwa, a leader of the indigenous organization El Molo Forum in Kenya. She explained that when the national and county governments decided to construct a resort on Lake Turkana, the traditional fishing community there was dispossessed of their territory.

The theme of dispossession is one that has reoccurred throughout the assembly. “Ocean grabbing is a complex practice where natural resources used by fishing communities on coastlines are being taken away in the interest of the corporate and private sectors,” said Naseegh Jaffer, WFFP’s general secretary who traveled from South Africa to be at the assembly.

Fishers throughout the assembly have stressed that ocean grabbing is not just about the seas; it also severely affects inland waterways that are often ignored. For instance in India, some two thirds of fish come from rivers far in the country’s interior. NFF has been working on this issue for nearly a decade now, and has demanded a national policy. The Indian movement works with its umbrella movement WFFP and other key allies to shore up international support for this critical process.

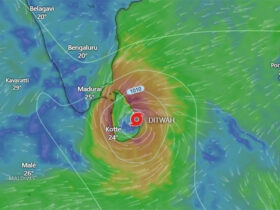

In recent years, climate change has accelerated the suffering of small-scale fishers, adding a layer of complexity and urgency to the enclosure of oceans and other water bodies. Rising sea levels push coastal fishers farther inland, and there, salinity intrusion destroys freshwater resources. From the Caribbean islands to the estuaries of Bangladesh, more frequent and increasingly powerful hurricanes and cyclones have hit marginalized fishing communities the hardest.

As small-scale food providers, fishers recognize that securing their livelihood and protecting their natural environment is a political act that requires intricate organizing at multiple levels.

A key starting point to achieve such victories is demanding food sovereignty, the political project and proposal that rejects the notion that food is a commodity. Food sovereignty places food providers and consumers at the heart of decision-making processes, and is deeply rooted in local production. It was put forth by La Vía Campesina, the international peasant movement that is a close ally to WFFP and that sent a delegation to the assembly currently taking place in Delhi.

One strategy for achieving food sovereignty is through agroecology, building local markets through ecological methods grounded in ancestral knowledge. Fatou Sylla, a WFFP member from an artisanal fishing union in Guinea expanded on the importance of markets. “We have managed to build a network of 56 cooperatives of women who smoke and sell fish,” she said, adding, “This is a way of defending our territory.”

Peasants who grow crops point out that their agroecological methods sequester carbon in the soil, therefore curbing global warming and punching back against climate change. Likewise, small-scale fishing practices protect against climate change by allowing fish stocks to repopulate, preserving seagrass and mangrove ecosystems, and ultimately reducing ocean acidification in the process. Both instances are political acts of protecting territorial rights.

“Agro is about agriculture, and ecology is about environment. We initially believed that it was not about us as fisher peoples,” Naseegh Jaffer reflected, “But when you put that all together, agroecology is a way of achieving food sovereignty. And it is a reflection of what we have been talking about all along.”

Clearly, today’s political battles against ocean and inland waterway enclosure are ones that must be fought uphill. But fishers are already entrenched in such struggles and committed to doing whatever it takes to win them. In Delhi, this seventh general assembly of a growing movement is proving to be a tipping point, where concrete alliances and strategic actions have the power to turn the tide on natural resource grabs—one community at a time.

Leave a Reply